Starting with your earliest family history, tell us about your great-grandfather.

My great-grandfather's name was Reinhold Finck. He came to San Antonio from New Orleans in 1852 that was sixteen years after the Alamo and he published a newspaper. As a matter of fact, he did two one in English and one in German and did that here for, I'd say, eight or nine years.

My grandfather was born here in 1856. Then they had a big cholera epidemic in San Antonio. My great-grandfather took his family and went to Vera Cruz, where he had a brother. When they got to Vera Cruz, they had a cholera epidemic there too. So, they finally went back to New Orleans, where they had a yellow fever epidemic. Two of the children died from the yellow fever there. That’s some of the old history of the South—cholera and yellow fever were big things.

- Photo to the left, Bill Finck at the Texas Legislature in 1965

[Reinhold Finck] came from Württemberg, Germany. It was an independent country at that time. It had a king. He came to New Orleans to work with his uncle. They had a bus business. A bus in the 1840s and '50s was a horse-drawn carriage with seats in it. Had a little cover over it. And that was what they did. He was a language...he spoke seven languages, and that was his big thing. New Orleans was full of people that spoke different languages. He kept the customers happy by talking to them.

He worked for his uncle, who was a bachelor; the uncle was the consul for the country of Württemberg. [My great-grandmother] must have come with him. I don't know much about her. My grandfather was born here, and they had eight children. It was a big family.

What was your grandfather's name and when did he come here?

My grandfather's name was the same as mine, Henry William Finck. They called him Henry. He was born in '56 and came here [San Antonio] in '93. He was [figuring] thirty-seven. That sounds about right.

- Photo to the right, 1861 newspaper published by Reinhold Finck

My grandfather grew up in New Orleans and learned the cigar maker's trade there and did different kinds of work for other people in the cigar business in New Orleans and other places. In 1893 he came back to San Antonio, borrowed $1,000 on his life insurance, and capitalized a business—all with $1,000.

So he didn't have his own business in New Orleans, and he started one when he came here.

He worked for other people there. As a matter of fact, he managed somebody's cigar factory down there.

Did he choose San Antonio because of the weather, the dry climate?

[He came to San Antonio because] they thought he had tuberculosis, which, obviously, he didn't. They told him to come to a dry climate, which, obviously, San Antonio isn't either. But whatever it was, he came back to where he was born. Came here and, after a period of time, recovered from whatever it was and lived to be seventy-seven years old. He didn't have tuberculosis.

- Photo to the left, Reinhold Finck, great-grandfather of Bill Finck Sr.

San Antonio was a place people came when they had tuberculosis. They thought they got the gulf breezes up here.

Well, they did get that; they do have that.

Where did he start this business? Where was the building?

I don't know the exact address. It was out on Government Hill someplace. He lived upstairs and made cigars downstairs.

How did he get the tobacco?

Well, see, in those days, there were cigar factories everyplace you went. San Antonio being a big city, there were five or six cigar factories here. His old boss shipped him some tobacco. Someplace in my bag of tricks, I've got a letter from the guy which says, "We sent you a bale of stock," as he referred to it. "How did it work out? We miss you. Hope you do well there."

- Photo to the right, Henry William Finck, Bill Sr.'s grandfather and namesake, who started the cigar company

Is he the one who started the Travis Club? Or was that later?

The Travis Club was [founded] in 1890. It wasn't too much later. The Travis Club was a private club, and the old building is on our cigar box. If you remember back, it was the Elks Club downtown, cater-cornered from the St. Anthony Hotel. It was built in 1890; it was a multistory building, and it was the old-style club. It had rooms, like hotel rooms. And it had a ballroom. It had a swimming pool, a natatorium. In 1909 it must have been quite unusual. And, of course, a big card room, and a bar, and all the things that go with it.

And, of course, it was for men only, I presume.

Well, they had parties there, but I guess it was like a men's club. I can remember in my youth some of the old clubs, like the Fort Worth Club, had rooms. You stayed there. It had a dining room. Of course, there were, sure as the world, couples in the dining room, but they always had a card room, a men's card room and everything.

So Henry belonged to the Travis Club?

Charter member. He was a charter member of everything because everybody smoked cigars, and he got around with cigar-smoking people. He wasn't a charter member of the Rotary Club, but joined the first year that it was in existence. He came within a hair of being a charter member.

Do you know any of the other things he was a charter member of?

San Antonio Country Club. The Casino Club. San Antonio Manufacturers Association. Whatever it was, he belonged to it. He was a popular, intelligent guy and successful. He was solicited to join everything.

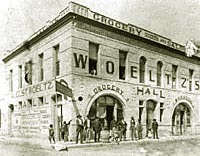

- Photo to the left, First home of the Finck Cigar Company, c. 1880

It's really fun to try to imagine back to those times.

Oh, yeah. I walk down the streets of downtown San Antonio, and I wonder what it looked like when my great-grandfather was here, and then what it looked like when my grandfather came back in '93. Lots of the buildings that they've remodeled now were built in '93.

Tell about naming the cigar. Did he name the cigar the Travis?

They made a private brand; it was made for the Travis Club. It was their brand. This was 1909 they started. World War I wasn't too much after that. And the old guys that belonged to the club were very patriotic. They made the club available to the young officers and officer students that were training around San Antonio. So, two things happened: one is, they liked the cigars so much they went back out to the base and demanded they put them in the PX and Officers' Club and everything; and another thing was that they used the club so much the old guys didn't like it so much anymore and quit going. The club died.

It was a unique cigar. The blend, that was what made it....

I don’t know. I think everybody made about the same thing in those days. They were good.

But he called it the Travis Club, and for a while they could only get it down there.

Right. It was a private brand.

- Photo to the right, Label featuring Travis Club building

Do you know the names of those early cigars, other than the Travis Club?

Yes. The first thing he made was called Finck Cheroots. They were sold three for a nickel, and my father said he used to go on his bicycle and sell a hundred cigars for two dollars.

And how much does a fine cigar cost today?

You can buy dollar cigars and two-dollar cigars and five-dollar cigars. Most of what we make is in the forty-five- to fifty-cent range.

He made Finck's Commerce; he made HWF, which were his initials; he made Little Fincks; he made Finck's Puritano; he made one called Resados, which, of course, is "seconds" in Spanish—rejects. It was very successful; they did a big thing with that. But because it’s a common name instead of a fixed name, somebody else made exactly the same thing, copied his box, and made trashy cigars and killed that one.

Where did he get his boxes?

I guess that they made them here in town. My father always liked to do everything himself. So, right after World War I, he bought a junker cigar box factory someplace and moved it down here and established his own. So, since then we've always made our own.

Did you used to make them out of plywood or something?

Well, plywood is real wood. It was tupelo gum or cedar cut in thin pieces and nailed together and paper edging put on the whole thing.

- Photo to the left, Travis Club cigar box

Are they still wood?

No, they're cardboard.

I love cigar boxes. I think everybody has associations with cigar boxes. Who did Henry W. Finck marry?

I said I don't know about my great-grandfather. I do, too. I was mixed up. Let me go back and tell you about him. Reinhold married Elizabeth Donauer. He and his uncle were in this bus business down there [in New Orleans]. Miss Donauer was Catholic, and my great-uncle, his uncle, was kind of a bigot. He didn't like the Catholic Church at all. So he told my great-grandfather, "If you don't marry the girl, I'll give you a hundred thousand dollars," which was right smart money. But they were in love, and he wasn't going to do it, so he finally married her, and they gave him fifty thousand dollars for his part of the business, which is still right smart money. He and his uncle split over….

Her being a Catholic. He met her in New Orleans, then?

Uh-huh. And she came with him, of course. They came immediately from New Orleans after they were married because there was a cholera epidemic happening there.

So they left the cholera epidemic and came to…what was the epidemic here?

It was cholera again, but this was years after he came, about eight years. The epidemics followed people around. They happen; they come and go.

While we're back on Reinhold, is there anything else about the German paper that he started that we should put in here?

I'm looking for a copy. I never got it. I got a copy of the English one called the San Antonio News. The German one was called the Texas Stadt Zeitung. It was in German, the way I understand it.

- Photo to the right, Finck Cigar sign in early San Antonio

As far as we know, he hadn't had any history in the newspaper business.

I don't think so. He probably came here and found something that looked interesting and bought it. They didn't write the newspaper. They would subscribe to the newspapers from other places and copy the articles out of other papers. You see, they didn't have a wire service. They didn't have any way of getting anything, so instead of inventing, all they could do was just get it mailed in some way and rewrite it. In fact, they just copied a lot of it. They wrote the local news, of course.

Do you have any idea what kind of circulation the German- language one had?

Don't have any idea. I'd be overjoyed if somebody would find a copy of the paper, find anything about the circulation, have a picture of where the thing was. It was on Soledad Street, but I don't know the exact address or anything.

I was asking you about your grandfather Henry.

My grandfather married in New Orleans. Her name was Nellie Kennedy [ Mary Ellen Kennedy]. They had children there. I think the last one was born in San Antonio, but my father was born in New Orleans. There was Aunt Mildred; Uncle Ike; Betty; Aunt Rita; Aunt Laura, who was a nun; and Joe. There were six of them. All lived in San Antonio.

Were any of them involved with the cigar company besides your father?

Oh, yes. Uncle Ike was, and Uncle Joe. All the boys were in the cigar factory.

Do you have any sense, back in that beginning, what the aura was? If there were eighteen cigar companies in San Antonio, there must have been a lot of cigar smoking going on.

Everybody smoked cigars. There weren't any cigarettes.

- Photo to the left, Travis Club decorated vehicle in a Battle of the Flowers Parade

Did women?

No. It was a man's thing. Everybody smoked cigars or a pipe or chewed tobacco; quite a few did all three. But cigars were probably the nicer thing.

So most men did smoke cigars.

Yes, probably. A substantial majority.

We talked before we started about three employees who had worked at the cigar factory for a long time. Who were they, and when did they begin?

As far as I go back, I think it was about 1916 or 1917. One is still working here. Rafaela Sanchez is still here. She's up in her mid-eighties, late-eighties. Works every day.

So they started as teenagers or even younger than that.

Oh, yeah, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen years old.

And then who were the others?

Rafaela Sanchez and San Juana Castilla. San Juana says she's coming back.

- Photo to the right, Travis Club delivery trucks

Was she sick?

She came back and worked for a couple of weeks. She rode to work, fell off the bus, and broke her arm, and so she's recuperating. She's coming back. Libby may come back, too, if she ever gets over her heart attack.

Libby Fernandez?

Liberata Fernandez, yes.

To what do you attribute the fact that your employees are so happy that they stay seventy years? That's got to be some sort of a record.

We're just such good guys. (Laughter)

That really is wonderful, though. How many employees do you have now?

I think we've got about seventy. We've always had people that worked here on and on and on forever. My old foreman retired ten years ago, fifteen years ago. He'd been here since he was just a kid. My box factory manager…we had a lot of people. At one time, I did a survey. I had a substantial number of people who had been here more than forty years, quite a few over fifty years. Libby and Rafaela and them, at that time, had been here close to sixty. We're all like a big dumb family that doesn't know any better than to make cigars. We just all sit around here and make cigars.

It used to all be by hand. Right?

Oh, yes. Everything was by hand. The ones over sixty, we didn't attempt to teach them to run the machines. We used them for examiners, for other hand things. Of course, they're excellent because they've been here so long—very loyal to the company. They were here when my father brought me here in a basket when I was a little baby. They make everybody else do right.

So there's a real sense of pride.

I hope so. We don't really talk about it, but everybody's still here. I used to have the two sets of sisters each. And then I've got daughters of those old employees; I've still got three or four of them here. And we've had a third generation.

- Photo to the right, Aunt Laura became Mother Helena, Secretary General of the Incarnate Word Order, in the mid-1930s

You've had third-generation workers?

Yeah. I don't think I've got any now. If I do, I don't know who they are. I can't think right off. I've got at least two girls whose mothers worked here, on and on. Girls—hell, they're my age, older than me, and I'm sixty.

When did the machines come in?

Daddy didn’t like the machines, so I did the machines.

Let's get the transition then, between your grandfather and your father.

Daddy, his name was Ed Finck. Edward Reinhold Finck was his real name. Everybody called him Ed Finck. He was probably the star member of the family. After he got out of the army, World War I, he came and was very active in the business. I'm not going to say he ran it. I think the old Germans ran it as long as they were around. He had a big lead part in it, though.

His father was still running it.

Right. My grandfather worked at the cigar factory, participated in it, until he...I think he had a stroke just before he died. Still, in '33 he was still here. And my father was with him [and] my uncle. My uncle's name was Oswald Henry, but everybody called him Ike, Uncle Ike. He was there, and he was close to Daddy's age. And then Uncle Joe, he was the kid. Everybody liked him real good. They had him out on the road selling all the time, stirring the salesmen up.

So where did you sell?

Well, my grandfather sold all over. He went pretty far out. Daddy, during the depression, kind of drew it in and did most of the Texas market. And that's what we do our big effort on now, where we've always been, in Texas where we're known.

- Photo to the left, (Left to right) Rafaela Sanchez and Liberata Fernandez, employed by Finck Cigar Company for over seventy years

Didn't they go out into towns? Was there a distributor? How was that worked?

They did it both ways. They had distributors, and they did some of it direct. The way I was told was that the salesmen would get on the train, because they didn't have cars, and go out to Del Rio, Uvalde, and get down and rent a hack. Make the stores there and then go out in the outlying towns from there, in the hack. Call on them, book the cigars, and then they'd ship them from here.

What's your earliest memory of the cigar factory? You said your dad brought you in a basket down here.

I don't remember that. We used to have Christmas parties. I've got a picture of me at a Christmas party, and I guess I was five years old, something like that. I have some vague recollection of that. In summertime, Daddy would bring me down. I'd sweep the floor, put tobacco stems in sacks, be in everybody's way. You know, just kind of play and be around.

You must have a memory, not a clear memory but a "feeling" memory, of the smells, machines—but you didn't have machines.

Tobacco and the guys, the way the factory was laid out and everything. We had tobacco, and we had lots of people doing the hand-made cigars, like several hundred. We had a multistory building, and it was all full of tobacco and offices and people and a shipping room.

San Antonio had eighteen different cigar manufacturers early on. Do you have a sense of why you were able to be competitive?

My grandfather, when he started out, he was a craftsman, and he would build showcases. And he'd put the showcase in, and the guy would put his cigars in it. He was a salesman; he was a businessman. He knew how to make them and he knew how to get rid of them, too. Everybody liked him. He was an intelligent guy. He got out and.… [When] Daddy was a little boy, he said he used to go out on his bicycle and peddle his cigars. You’ve got to. If you’re going to survive, you’ve got to do it.

Where did he get the tobacco? When did your family start having to travel around?

I don't think my grandfather ever traveled to buy tobacco. My daddy liked to travel. Of course, he had been around during the war and everything, and he started going to Cuba and Puerto Rico. He would buy the tobacco there and supervise the processing there. He’d probably go off for two or three months at a time. They used to buy Sumatra tobacco that was sold in Holland, and he would go to Amsterdam to the auction. We've always used, and still do use, a lot of Connecticut tobacco.

- Photo to the right, employee of Finck Cigar Company for over ____ years

People don't think of Connecticut—New England—as being tobacco country. Are there different tobaccos for cigars?

Oh, yes. It's a different seed grown in a different place; a different kind of cure, a different culture. It's quite different. There was a lot of tobacco grown in the Northeast. They still grow it in Connecticut; they still grow it in Pennsylvania. There was tobacco grown in New York State, in Ohio. There's still tobacco grown in Wisconsin.

I would have named all Southern states.

Cigar types. The Southern states, they're flue-cured for cigarettes and burley and chewing tobacco.

When did you go on your first tobacco-buying jaunt?

Daddy took me to Cuba when I was fourteen.

What do you remember about it? Did you go out to the farms?

Yeah, we went around to some farms, but what I remember best is the Havana tobacco warehouses, the people we did business with, how everybody was down there.

- Photo to the right, 1936 Finck Cigar Company Christmas party with 250-300 employees

What's a tobacco warehouse like?

Well, the one I remember was a multistory building. They had the tobacco there, and it was stacked in bales, stacked five bales high. The guys would go through and take the ones from the bottom and put them in the middle. Like, about every three months, they would rotate them because they cured better that way.

You wanted a sample of tobacco, you'd go in the warehouse, and they'd get these bales down, open them up, and you'd look at the tobacco, make a cigar out of it, and smoke it. We still do it that way.

You said, I guess, it takes eighteen months [to make] a cigar.

That's probably the average.